Hello everybody!

The last evening, have caught myself reading an entire ‘cluster’ of articles about air war over Ukraine, the Ukrainian and the Russian air defence systems and related topics. ‘Cluster’, because, essentially, one author is referring to another, who is referring the the third one, who in turn is referring to the first one, or the fourth one, or 5, 10, 15, 20 different other authors etc. And, ‘cluster’ also because all the articles in question were, even when put together, combined, offering little else but ‘shopping lists’. See, ‘Ukrainian air defences are including these fighter jets, and that air defence system, and this and that…’ (read: lists of equipment), and ‘Russian air defences are including this, and that, and this and that’…and then the Ukrainian missiles and attack-UAVs are including this, and this and this, and the Russian this, and this and this… and becasue it’s that way, these air defences are great, and the other not, or having this or that kind of a problem..

No, I’m not belittling anybody. Just concluding that lots of people are making things far too simple - for themselves, and for their readers, and thus misinforming, rather than explaining.

Point is… well, my first point today is: sorry boys and girls, that’s not how air warfare is working. Therefore, I’ll now waste your time trying to explain how it does work.

***

Communications

Communications are the essence of air warfare. So much so that - oversimplified, and for example - without communications the Ukrainian integrated air defence system (IADS) is best summarised by this map:

How? You mean, the map is showing nothing but Ukraine with its major cities and neighbouring states?

Well, yes. It does. However, and as explained above: it is also showing the Ukrainian IADS - without communications.

Because, without communications nothing works in air warfare.

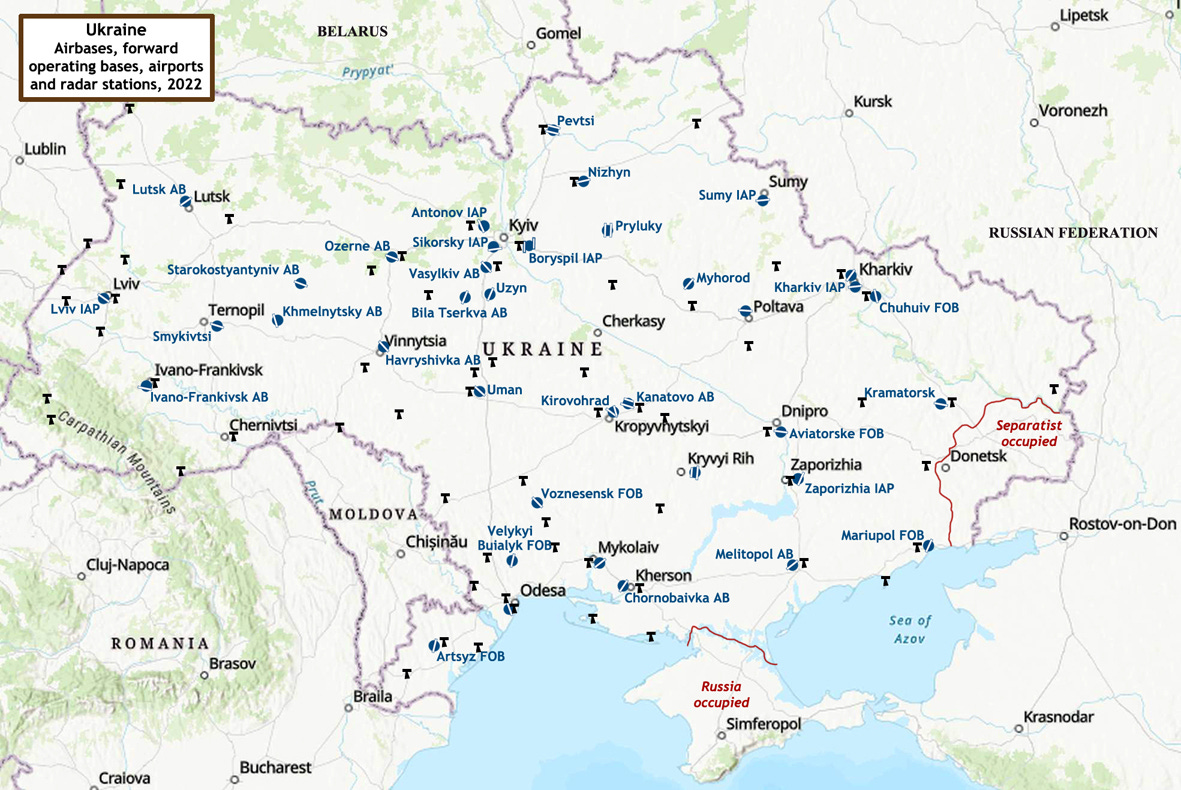

Modern-day military communications are ‘complex to explain’. In the case of Ukraine, and before the Russian invasion of 2022, their core was a network of cables connecting principal command nodes - like the headquarters of the Ukrainian Air Force and Air Defence Force (PSZSU), in Vinnitsya - with principal sensors: radar stations. The exact positions of cables in question is usually a (relatively) well-guarded secret, which is why hardly anybody is talking about them. Instead, people tend to illustrate the radar network, with maps like this one - (essentially) depicting the position of some 70 radar stations operated by the PSZSU as of early 2022:

However, that’s a much oversimplified presentation. Alone because it’s neither showing major airbases (ABs), nor forward operating bases (FOBs), nor major garrisons of PSZSU’s ground-based air defence units. Even less so something like ‘present-times disposition’ of ground-based air defence units (which, of course, is really a ‘top secret’ topic). Point is: it’s not only time-consuming to collect the related data and add it to any such maps, but also the resulting maps tend to get overcrowded. Just for example, this would be a map of major ABs, FOBs and radar stations of the PSZSU as of early 2022:

From this point, things can only get even more complex. Consider adding the major command nodes, then their cable connections, then think about adding the type of radar operated at each of radar stations in question; the type of identification friend-or-foe systems (IFF) installed on that radar; then add their methods of communication - satellite communications, tactical radio networks, mesh networks, cellular networks, secure communication systems, cable connections… - then add electronic support measures systems (ESM; like Kolchuga, of which Ukraine had some 26 as of 2022, just for example)… sufficient to say: it’s not only hard to find out where is what, or that very few people will be able draw related maps, but the resulting maps are regularly going to be obsolete in a matter of minutes of being drawn, and there are almost as few people capable and ready to really read the resulting maps. Therefore, we all - anybody doing things like I do, which is monitoring and commenting this war/air war - are oversimplifying. And that all the time.

For example: we tend to explain that the Ukrainian IADS was (and remains) headquartered in Vinnitsya, and is comprising a network of multi-layered, interconnected sensors, command and control nodes, and weapons systems - organised on regional basis (West, Centre, East, and South). We then tend to go on explaining how many units are equipped with what kind of combat aircraft, how many with what kind of surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), how many with other weapons systems, ESM-systems - and where is what unit home-based - etc. And that’s fine that way.

However, and hand on heart, none of such descriptions really ‘works’, because yes: air warfare is complex, highly technical, and depending on so many entirely different factors - the essence of which was, is, and is going to remain: communication. Whatever are the command nodes, whatever weapons systems, the people operating them must be able to communicate with each other - and that in real time - or there is simply no IADS. You’ll see that I’ll be coming back to this issue again and again throughout this feature.

***

Active & Passive Systems

Another topic next-to-never discussed when it comes to air warfare, but to which I’m going to return throughout this feature, is that, generally, both communication systems and sensors/detection systems can be sorted into two categories:

Active systems are those that emit one or another type of emissions. Usually, that’s electromagnetic emissions. For example: radar is an active system, radio is one, satellite communications, too. Passive systems are those not emitting anything at all. Considering one can detect a radar emitter from something like two times its effective range - for example: emissions of a radar with detection and tracking range of 200km, can be detected from out to 400km - this is extremely important. Simply because ‘any decent armed force’ nowadays is equipped with passive ESM systems made to detect such emissions and pinpoint the position of emitters.

Now, because at war, ‘when bullets start to fly’ nobody is running around yelling, ‘shot me, shot me first’, when one has pinpointed the emitter, one knows where is the enemy: the pinpointing, localising the enemy is something like 50% (and, often enough: much more) of ‘fighting’ that enemy. Sometimes, it’s 100%: when the Party A knows where is Party B, while Party A is denying the Party B both the knowledge, and the ability to find out where is the Party A… that’s then resulting in superior situational awareness, and thus very one-sided wars. The Party A is winning ‘with ease’, the Party B losing most, if not all the time…

Because of this, you can always comfortably bet your annual income on two fundamental principles:

…simply because emitting is ‘bad’ (enabling the enemy to at least detect, if not actually find you), while not emitting, or doing that in the form undetectable by the enemy is ‘good’.

Because of this, before going on, please memorise this therm: EMCON. Stands for emission control. Memorise that at an air war like this one in Ukraine, the mass of involved forces (with notable exceptions to which I’m going to return, time and again), is most of the time operating ‘under total EMCON’: it’s not emitting any kind of electromagnetic emissions at all.

(EMCON is why, just for example: people serving in air defence are strictly prohibited from activating their cell phones, private or not, all the time… notable exceptions are such like an officer of the Pakistani Army, operating Chinese-made HQ-9 SAMs in the middle of Karachi at the time of the war with India, in May this year, and then not only taking photos of camouflaged positions of his unit, but also bragging with these in the social media, so the Indian intel could better geolocate the same… hope, I need not explaining the consequences…)

***

Ranges and Envelopes

A standard practice since earlier times, over the last 30 years in particular it became a sort of dogma to ‘gauge’ capabilities of different military systems by their advertised technical specifications. Say, the manufacturer XY said its weapons system, or radar, or whatever else, can fly this fast, or can detect from this or that range…

At earlier times, that was perfectly OK. At the times the principal weapon of combat aircraft was a machine gun or autocannon - and that was that way well into the 1960s, often into the 1970s and later - things were simple. A machine gun is rarely having a range of more than 1000 metres. An autocannon perhaps two times as much. Sure, in combat, ranges were often down to 100-400 metres - simply because, except in the case of bombers, the size of contemporary combat aircraft as seen from behind from any longer range was comparable in size to the dot at the end of this sentence.

The introduction to service of supersonic jets and guided missiles made things extremely complex. Ranges and speeds grew immensely. Moreover, over the last 20-30 years, the mass of reporting about military affairs became dominated by ‘industry’, rather than ‘operations’ - and resulting ‘combat experiences’. The research about combat experiences became ever more complex also because modern-day weapons systems remain in service much longer than this was the case before: no user is keen to make his/her system obsolete by talking too much about it…

Why am I explaining this?

I do not brag about working in different fashion, but: I am pointing out that instead of ‘range’, as is usually done, I tend to use the term ‘envelope’. Advertisements are advertisements: manufacturers are proud of- and love the stuff they have developed, and like to brag about its maximum capabilities: indeed, they even must brag, or their stuff is not going to sell, and they’re going to go bankrupt, not remain manufacturers. However, accepting advertisements for bare money - especially in combination with ignorance for elementary physical laws - is 1000% certain to lead to massive misunderstandings, and lots of disappointments.

Actually, air warfare is a four-dimensional affair, PLUS: it’s influenced not only by ‘obvious’ physical laws, but also the Earth’s curvature (do we really have to discuss that?), terrain, weather, atmospheric conditions at different altitudes etc. Moreover, in a war like this one in Ukraine, neither party is sitting idle and waiting to get hit, but all the time deploying countermeasures. As a result, and oversimplified: stuff having an advertised range of 100- or 200km, is unlikely to be effective over more than 50- to 100km, respectively. More often than not: even much less than that.

It’s similar in regards of radar: the fact some manufacturer is advertising its radar system as having a max detection range of (for example) 100km, means anything else but that this radar is always, 1000% sure, going to detect everything it needs to detect within range of 100km. On the contrary: especially when it comes to radars it’s the volume of airspace they can scan, the scanning rate, the resolution, terrain, weather etc - that are far more important than anything else.

These are the reasons why I’m often discussing ‘envelopes’, or overemphasising combat experiences above the ‘range’, and rarely talking about technical specifications or advertised ranges. You’ll see a lot of this as I go on, too…

***

Manoeuvre

Air warfare is a discipline in which everything is moving at stunning speeds. Everything. Starting with related research and development (R&D). Imagine: the first powered (and manned) flight took place mere 122 years ago. Only 66 years later - and 56 years ago - humans were already flying to the Moon…

Now, surely, there was a lots of public degeneration in the meantime. And, say, the period of the (really: RELATIVE) ‘peace’ in the last 30 years, appeared to have slowed down everything. However, the R&D never stood still. It was delayed, sure, but still: all the time advancing, inventing ever more advanced solutions. Since everybody is fighting some kind of war - i.e. since around 2015-2020 - this is even more the case. The result is that what people like me tend to think they ‘know’, right now, is almost certain to become obsolete - often in a matter of minutes. Therefore: don’t be surprised if I don’t know, miss, or forget about different things.

That with ‘stunning speeds’ is even more valid for the speeds at which ‘things’ making air warfare are moving. At war, combat aircraft (cruise missiles, too) are usually ‘cruising’ at something like Mach 0.9: 1111 km/h; ‘slowest’ missiles nowadays are underway at anything between that Mach 0.9 and Mach 2,5 (3087km/h); the fastest at Mach 4 (4939km/h) to Mach 10+ (12348km/h and more)….where that with the Mach-factor is relative: permit me to remind you that the ‘speed of sound’ (significantly) varies with the altitude above the sea level and thus the air density…

Sure, the attack-UAVs are moving at much slower speeds: depending on propulsion, this is usually anywhere between 75- and 120km/h, or around 300-400km/h. However, that’s still much faster than any of ground-based weapons systems.

The ‘negative’ aspect of this is that air power, actually, has no standing power: the requirement for speed and altitude is requiring lots of energy, which in turn means that neither aircraft, nor missiles or attack UAVs can carry enough fuel to remain in the combat zone for longer than between few seconds and few minutes. Nor is this advisable: any missiles, or aircraft, or attack UAVs remaining within the combat zone for any longer than absolutely necessary - are getting easier to shot down with every second.

Overall: in comparison to air warfare, ground warfare is ‘static’. In comparison to electromagnetic emissions, aircraft, missiles, and UAVs… not only tanks, but especially ground air defence vehicles are moving at such slow speeds, that air power has it easy to outmanoeuvre and outrun anything tied to the ground. This is why air warfare is not only hard to follow, but also hard to explain: it’s nearly always so that lots of things are happening at the same time, all in a matter of milliseconds and then, just seconds later, there is nothing of this to be seen. The air power is, literally, ‘away’.

This, the' ‘temporary’ nature of air warfare is of crucial importance to keep in mind for understanding two related things.

1.) As hard as it is for people (or weapons systems) on the ground to track developments in the air, it’s even harder for people (or weapons systems) in the air to track developments on the ground. Even fastest missiles still need ‘minutes’ to reach their targets. For example, this results in the fact that, no matter how slow, ‘mobility’ of ground-based air defences still matters. It’s often enough to move them just by 200-500 metres, and the ‘air power’ (manned or not) is going to miss them - because it does not know their new position on time. Which is just another reason why ‘communication’ is so important…

2.) The ‘mobility’ of ground-based air defences is still a (very) relative factor. The mass of ‘mobile’ radars and air defence systems are ‘mobile’ only in terms of one being able to turn them off and then pack them (usually within 5-30 minutes); they are wheeled, often motorised too, and thus it’s ‘easy’ to re-deploy them somewhere else within relatively short periods of time (again: 5-30 minutes). However, there are only very few ‘mobile’ ground-based air defence systems that can actually shoot while moving, the mass of these are short-ranged, and their precision is still lower than those that are must stop and stand still to open fire. On the contrary, the mass of ‘mobile’ ground-based air defences first have to stop, then calibrate their systems, and then have to power up - before they can open fire - which, depending on the system in question, is also taking 5-30 minutes (if not longer). Typical examples for such ‘mobile’ systems would be the Russian S-400 or the US-made FIM-104 Patriot. Actually, both are ‘road mobile’ (only), and neither is capable of opening fire while underway: they first have to stop, then have to be calibrated, and then to power up before becoming ready for combat operations.

I’m mentioning this because, as I’m going to explain further below: this with ‘manoeuvre’ - and ‘mobility’ - is one of principal factors why when it comes to air defence, the ‘flying stuff’ (whether combat aircraft, or modern-day interceptor drones) is always in the position of distinct advantage vis-a-vis ground-based air defences. However, because of that with ‘fuel’, and the resulting ‘endurance’, that’s always of very temporary nature.

***

Strategy

Having explained the ‘elementary’ things one needs to always keep in mind, now lets move over to ‘strategy’ (before following up with what appears to be most interesting and fascinating for most of people: ‘tactics’).

Here I’ve got to start with the start: a ‘shopping list’ in style of, ‘Russia (or Ukraine, or India, or Pakistan, or enter the name of the country you prefer) has so and so many of these and those weapons systems, and so many of those weapons systems’, or similar - is entirely pointless. Principally because

What am I talking about now…?

About strategy, which in turn is dictating tactics - which is something I’ve explained two nights ago. And as explained at that opportunity, neither Ukraine, nor its ‘western Allies’ have a strategy for this war.

How do I know?

It’s simple:

Here a brilliant example for results of such miserable failures by the politics (in Kyiv, and in ‘Brüssels’). About a week or so ago, the media was full of reports about the delivery of the fourth Skyshield air defence system to Ukraine. Hand on heart: alone the designation… let it glide down your tongue: S K Y S H I E L D… oh man, this is so cool, so great, and so dramatic at the same time, one can outright visualise it alone due to this designation - and I’m sure a number of ladies has fainted now…

But, lets have a look at the impact of those four Skyshield systems on the air defence capability of the PSZSU in grand total - in form of this map of Ukraine:

Erm… you mean, it’s the same, empty map of Ukraine with its cities and neighbouring countries like at the start of this feature, all over again? Oh come on: admit it. Actually, you can’t discover the four blue dots representing the volume of the Ukrainian airspace the four Skyshield air defence systems protecting (theoretically) Lutsk, Lviv, (downtown of) Kyiv, and Vinnytsia can cover. You probably didn’t even try…

…which is really strange, because I’ve clearly marked them, and yet… tsk, tsk, tsk…

Well, but that’s precisely the point. Sure, technical specifications of the Skyshield sound great. The designation is so sexy. And it looks so sexy, too. But, as much as it also sounds great that the calculated (by its manufacturer) cost per single attack UAV shot down is below €5000, in grand total, its technical specifications are defining the Skyshield as a (literally) ‘point defence system’.

By their very nature, point defence systems are at the end of the food chain in aerial warfare. They’re the ‘last ditch defence’: stuff made for the case that all the other sorts of defensive measures have failed.

Moreover: as much as ‘mobile’ (as far as installed on a tracked chassis), the Skyshield can’t protect more but a piece of airspace in a circle of approximately 1,500 metres around its position. That’s a circle of 3km/3,000m.

…while Ukraine is stretching (on its East-West axis) over some 1,300km (plus)… and… well, that notorious itch in my small toe is telling me that, should I now venture into measuring the total length of a radius of, say, 10km around every major urban centre of Ukraine, every major power plant, plus every major transformation station… this length might be several times longer…

Finally, their numbers: we’ve got the November 2025, it’s more than 3,5 years since the start of Russia’s all-out invasion, and only now are there four Skyshield systems in Ukraine. Had the zombie idiots in Berlin and similar places, back in 2002, listened to so many (including your very own) explaining them that this war can’t be over in a matter of weeks nor months, and about the necessity to promptly launch major rearmament projects, so to re-arm Ukraine as first, and themselves as second… well, some two years later (which would be sometimes in 2024), the production would’ve been underway and, by now (in 2025) enabling NATO to deliver some, say, 40-50 Skyshield systems to Ukraine. Enabling the PSZSU to protect a similar number of crucially important installations around the country.

This, simply, didn’t happen. Because neither Kyiv, nor Berlin, and thus no Brüssel ever developed a strategy for defending Ukraine from Russia. This is why now (in 2025), Ukraine has exactly four Skyshield systems in operations, and these are covering as much as explained above - while… oh wait, this is getting better and better: the next year, Kyiv might count on getting another handful of additional Skyshields… or so..

But, never mind: go on explaining me that the only strategy for Ukraine that does matter, is the one to kill yet more Russians. And similar - all of which was proven as working so well the last 3,5 years, right?

This text is published with the permission of the author. First published here.