The central paradox of the Ukraine war is this: Russia desperately needs the war to end, while Vladimir Putin is increasingly dependent on its continuation. These interests are no longer aligned—and the gap between them is widening.

For Russia as a state, the war has become an economic, demographic, and institutional drain. For Putin as a ruler, however, the war has become a political trap. Ending it now would force him to explain sacrifices that can no longer be credibly justified, while continuing it deepens the very damage Russia cannot sustain indefinitely.

For Putin, the war is no longer about victory. It is about narrative control and personal survival.

A negotiated end—especially one short of clear victory—would raise unavoidable questions: Why the casualties? Why the economic hardship? Why the defacto-mobilization? Why the lies? These questions are manageable during war. They are much less so in peace.

Contrary to earlier assumptions, the war does not unify Russia’s elites. Elites are looking for the door. Whether that door leads to a fall from their penthouse apartment remains to be seen. Sanctions, asset seizures, travel restrictions, and shrinking margins have taxed loyalty.

Even more threatening is the issue of the army itself.

Putin and the elites are scared to bring home a war-torn, abused, and lied-to army. This is not an abstract concern. Returning soldiers would carry lived experience that directly contradicts state propaganda. Any army vet can tell the truth better than Putin can.

Readers searching for high-quality information - such as yourself - might prefer to support my work with a one time contribution vs a subscription. https://buymeacoffee.com/researchukraine

The Russian military—despite catastrophic losses—is lionized by Russian society. Soldiers are portrayed as heroes defending the nation against the West. When they return, those “heroes” will command moral authority. They will have trust—equal to or greater than Putin’s—precisely because they paid the price. It makes me wonder, will the gulags in Siberia be full of returning fighters, just like during and after WWII?

A demobilized force with shared grievances, informal networks, and public legitimacy is a classic destabilizing factor in authoritarian systems. Ending the war would mean reabsorbing hundreds of thousands of men trained in violence, aware of corruption, and conscious of being misled. Continuing the war postpones that reckoning. Possibly giving Putin enough time to find another conflict to dump these men into. Africa, Syria, Venezuela? N. Korea?

Finally, war provides procedural cover. Repression, censorship, budget secrecy, emergency powers, and elite discipline are all justified by ongoing conflict. Peace would remove the rationale for extraordinary measures. From Putin’s perspective, that is the worst possible outcome.

For Russia as a country, the calculus is far more straightforward.

Economically, the strain is mounting. Energy revenues—the backbone of the Russian budget—have declined significantly under western sanctions as well as Ukraine’s Long Range Sanctions. Wartime spending has distorted growth, crowding out civilian investment resulting in masked structural weakness. What looks like resilience is increasingly forced mobilization of resources.

Consumer behavior reflects this reality. Wartime stimulus initially supported consumption, but household confidence is weakening as prices rise, savings fall, and expectations deteriorate. Regions are hollowed out as labor is pulled into the military or defense industry, exacerbating demographic decline that predated the war.

Strategically, Russia is becoming more isolated and less secure. Dependence on China has deepened, access to markets has narrowed, and long-term competitiveness has eroded. Even a frozen conflict would ease some pressure; a prolonged high-intensity war compounds it.

Socially, the costs are corrosive. Casualties are unevenly distributed, hitting poorer and peripheral regions hardest. This strains the implicit social contract: political passivity in exchange for stability. As stability erodes, repression must increase—an expensive and brittle substitute concentrated in the areas most likely to produce rebellion.

From a state perspective, ending the war—even inconclusively—would reduce economic bleed, slow demographic damage, and open limited pathways to normalization. It would not solve Russia’s problems, but it would stop making them worse.

Putin cannot easily end the war because peace threatens him personally. Russia cannot afford to continue the war because it threatens the state itself.

This is the Putin Paradox: the longer the war goes on, the safer Putin may be in the short term—and the weaker Russia becomes in the long term. The interests of ruler and country have diverged so sharply that policy has become a hostage to regime survival.

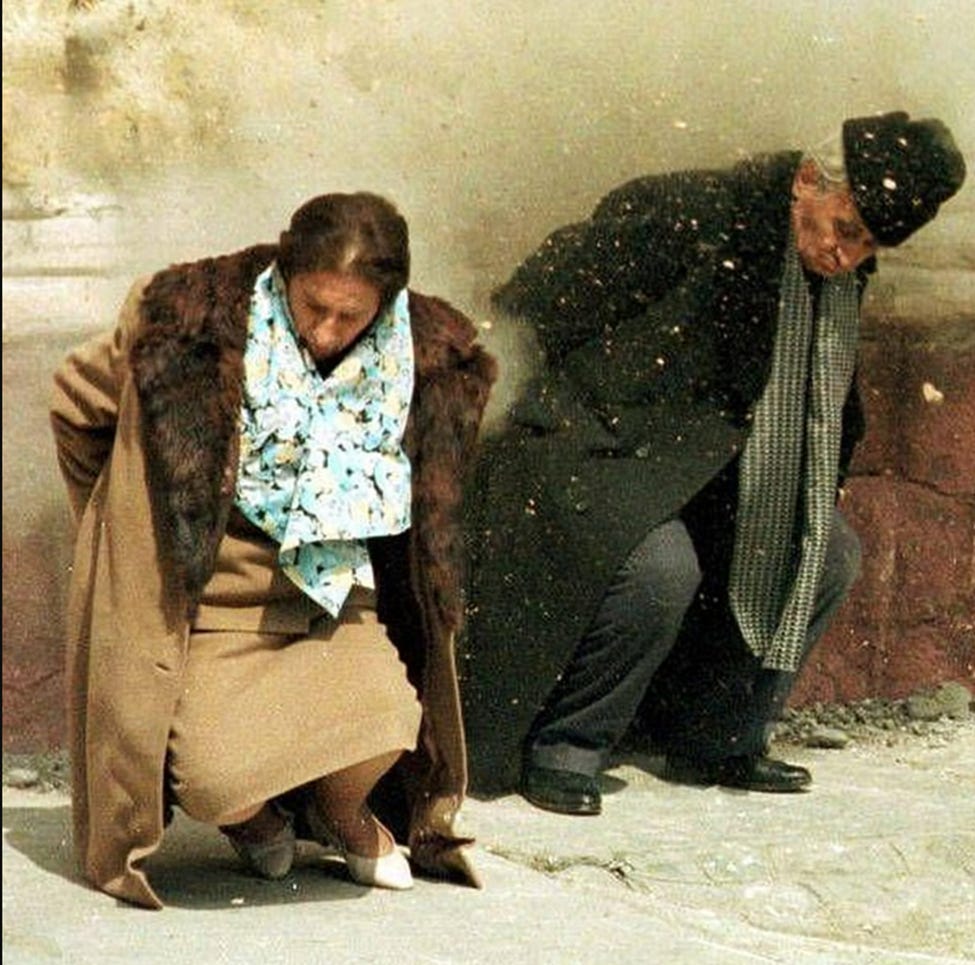

History suggests such gaps do not close gently. And Christmas 1989 stays on Putin’s mind.

Benjamin Cook continues to travel to, often lives in, and works in Ukraine, a connection spanning more than 14 years. He holds an MA in International Security and Conflict Studies from Dublin City University and has consulted with journalists and intelligence professionals on AI in drones, U.S. military technology, and open-source intelligence (OSINT) related to the war in Ukraine. He is co-founder of the nonprofit UAO, working in southern Ukraine. You can find Mr. Cook between Odesa, Ukraine; Charleston, South Carolina; and Tucson, Arizona.

● Reuters – Russian energy revenues, fiscal strain, sanctions impact

● The Economist – Russian wartime economy, elite behavior, sustainability

● International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) – Military losses and force structure

● Institute for the Study of War (ISW) – Russian domestic politics and mobilization

● Levada Center (pre-designation polling) – Public attitudes toward the war

● RAND Corporation – Authoritarian regime stability under prolonged conflict

This text is published with the permission of the author. First published here.